Vladivostok Parishioner Preserves Bishop’s Relics

Miroslava Efimova

Archivist of the Catholic Parish of the Most Holy Mother of God

Translated by Janusz Zaleski

In July 2000, the Roman Catholic parish of the Most Holy Mother of God in Vladivostok celebrated the 145th anniversary of the birth of Bishop Karol Sliwowski. Inside the cathedral was a small exhibition of the bishop’s photos and documents. There were also his briefcase with the initials “K.S.,” an inkpot, and some writing utensils.

At the time, these items and the large marble crucifix in the cathedral were the only historical memorabilia in the possession of the parish.

Here is the story of how the bishop’s items were preserved and how they found their way back to the parish. Unique memorabilia are often safeguarded by families and are passed with care from generation to generation. In this case, the guardian of the bishop’s personal effects happened to be an old Vladivostok parishioner, Regina Stanko, who later came to reside in Tomsk, South Central Siberia.

When she learned from TV news about the reopening of the Roman Catholic parish in Vladivostok, she contacted the Pastor Fr. Myron Effing. She also sent Bishop Sliwowski’s personal effects, and provided valuable facts and information about his last years.

Regina disclosed that the bishop was not sent to a concentration camp, but was exiled to the Vladivostok suburb of Sedanka under house arrest. There, in a small dwelling, he remained under the care of a young parishioner, Sister Casimira Piotrowska, until his death in 1933 at the age of 85.

In her letter, Regina enclosed the picture of the bishop’s grave. The date of death and the name were clearly visible on the tombstone.

Thus, the parish established correspondence with Regina, through which the story of the Stanko family became known. Regina’s father Stanislaw Stanko was a Pole living in the western Russian province of Witebsk. After the Russo-Japanese War of 1904, he arrived in Vladivostok and worked in the construction of the local fortress. Later, he was employed in the engineering office. When the Soviets established a new government in Vladivostok, Stanko worked as a railway engineer and lived with his family near the railroad Station “Kilometer 6.” There on a small lot, he had a house with a cellar, and a barn with one cow, one pig, and some chickens.

After the arrest of Fr. Jurkiewicz, pastor of the Vladivostok parish, and after the exile of Bishop Sliwowski to Sedanka, Mrs. Stanko began daily sending her 10-year-old daughter Regina with milk for the bishop. The bishop lived in the house of Casimira Piotrowska. As long as his health permitted, the bishop enjoyed the visits of Stanislaw Stanko and the long conversations with him in the Polish language. Unfortunately, while under house arrest, the bishop’s health deteriorated quickly. On January 5, 1933, when Regina arrived as usual, she was greeted by Casimira Piotrowska with these words: “The milk for the bishop is no longer needed. He does not need anything anymore.”

Little Regina attended the bishop’s funeral on January 6, 1933 at the Sedanka Cemetery. The coffin was made from zinc, because Casimira Piotrowska intended to transfer the bishop’s remains to Poland. The bishop was dressed in white garments and a gold-colored biretta. He was wearing a bishop’s ring on his finger and had an ornamental crosier in the coffin.

Three days after his burial, his grave was opened and robbed. The ring and the crosier were taken. The remains of the bishop were later placed in a simple wooden coffin and reburied in a different grave. Casimira tried to obtain permission to transport the bishop’s remains to Poland, but her request was categorically denied.

During the summer of 1934, Regina and Casimira often visited the bishop’s grave. It was then that the picture of the gravesite was taken. Soon after, Casirmira distributed the bishop’s belongings among the parishioners. The Stanko family received several things which were placed in a special wooden chest. The chest was always safeguarded, closed, and the children never knew the contents of it.

One night in August 1938, Stanislaw Stanko was arrested and the NKWD (later KGB) took the contents of the bishop’s chest. The Stanko family, mother, son and daughter, were ordered to go within ten days to Siberia.

Mother Stanko took with her the bishop’s chest with his remaining items: a briefcase initialed “K.S.,” the old inkpot, and writing utensils. Regina described in her letters how oppressive was the life in Tomsk, Siberia. They were branded as the enemies of the people. The family had to live in the house of the father’s distant relatives, who were unhappy to accommodate the persecuted newcomers.

Regina wrote in one of her letters, “The wife of my cousin was from a family of loyal Soviet revolutionaries and worked as a NKWD medic. Thus we were under constant vigilance at home. Within a year, my father was released from the hard labor camp, but was too ill to work or to help the family. He died shortly after his release. At the same time, we received a letter from Reverend Jurkiewicz. He had been arrested in December 1931 in Vladivostok and sentenced to ten years of hard labor in a gulag in Siberia. He obtained our address in Tomsk probably from one of the prisoners, who met my father in the labor camp. The Reverend was begging us for wool socks and bacon. My mother mailed him a package in spite of our poverty. We never heard from him again.”

Regina’s brother was killed in 1940 during the Russo-Finnish War. Regina remained alone with her mother. Soon war broke out with Germany and lack of bread and very hard times followed. Nevertheless, the Stankos never attempted to exchange the bishop’s items for food.

Regina attended a medical institute and joined the army as a physician. After a very eventful life, she brought up two daughters and lives now with her grandchildren. All of them are faithful Roman Catholics.

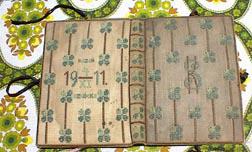

Regina resides in Tomsk, but she never forgot the Vladivostok friends and the deceased priests Bishop Sliwowski and Reverend Jurkiewicz. In her correspondence with the Vladivostok parishioners, she indicated how to find all the bishop’s confiscated items. Thus one of the parishioners, Jadwiga Zielinska, located a list of the bishop’s personal effects seized in the house of the Stanko family: a tea set, a coffee jar, album, note-book, shotgun, binoculars, Polish language books, ornamental box and a ship model. The police authorities gave the following reply to the parish inquiry: “A review of the records of Stanislaw Stanko arrested by NKWD in 1938 did not produce proof that any items confiscated in his house were the property of the bishop or of the parish.”

This eliminated any possibility of recovering the bishop’s or the parish’s memorabilia other than those items which were saved by Regina Stanko.

The parish is very grateful to her for being a good guardian of the historical memorabilia. Despite the great distance between Tomsk and Vladivostok, Regina remains a dear parishioner who once was baptized in the cathedral and received First Holy Communion in Vladivostok from Bishop Sliwowski. The hearts of the parishioners will always be with her repeating together the same prayer—“O Holy Father, Almighty and Eternal God, have mercy on us.”

Additional information appears in the September 1, 2003 (Number 53) issue of the Vladivostok Sunrise newsletter.